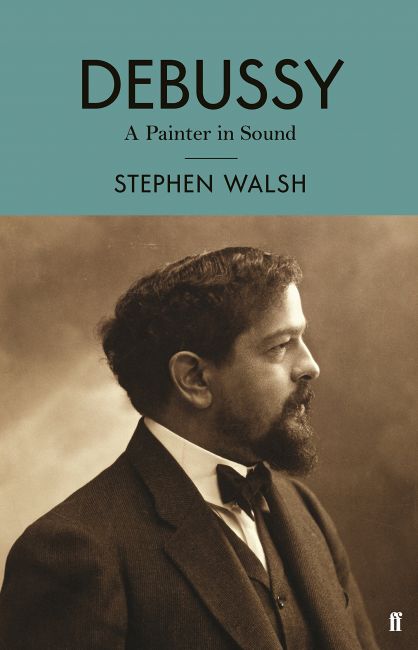

DEBUSSY: A Painter in Sound

Debussy: A Painter in Sound by Stephen Walsh

Faber and Faber 2018

Review by Paul Roberts

International Piano, September/October 2018

‘I am not aware of any book that adopts a strategy quite like mine,’ writes Stephen Walsh in the introduction to this biography of Claude Debussy, published to coincide with the centenary of the composer’s death in 1918. The particular strategy produces ‘a biography of sorts,’ but one that ‘sets out to treat Debussy’s music as the crucial expression of his intellectual life, rather than a slightly annoying series of incidents that hold up the story without adding much of narrative interest. Indeed Walsh succeeds so brilliantly in his aim that the music itself becomes the narrative, even to the point where for me it is the biographical parts that hold it up. Yet one more account of Debussy and the married Marie Vasnier or the unmarried green-eyed Gaby - that so enthralled me as a teenager - are unlikely to change the world. Walsh keeps music, art and ideas constantly in focus, and the life respectfully in the background. Debussy was a perfectly normal human being in all respects apart from his genius. As he said, ‘Why can’t I be allowed to get divorced [and we might add have affairs and be rude to people] like everyone else?’

Debussy, writes Walsh, ‘is a composer loved by many who respond instinctively to the beauty of his music without it occurring to them that he might be seriously regarded as one of the very greatest, which is roughly speaking my view’ (and I should say it is mine too). These many, then, are his target audience, though surely it was unnecessary for him, or his editor, to define such musical terms as cadence and arpeggio, especially when they assume the reader’s knowledge of Ruskin and Schopenhauer.

I came away from this book in a good mood, delighted to have familiar issues appraised from a new angle, to be reminded of what I’d forgotten, and to have confirmed again the sheer sensual beauty of an art whose enigmatic qualities are a sign, a definition almost, of its power. ‘To describe this music,’ Walsh writes of one of the piano Images (‘Et la lune…’), ‘the parallel triads, the two-part counterpoints of vaguely oriental melody, the different variants of the opening chord sequence, is easy enough. To explain its unique, haunting beauty and its formal perfection is another matter.’ But somehow as he moves to and fro across the whole range of Debussy’s oeuvre (it is a huge achievement that the book covers virtually all the music without ever appearing to be ticking boxes), a kind of awed explanation emerges in the accumulation of descriptive and comparative detail. This is all achieved without a single musical quotation. If one knows the music one can virtually hear it as Walsh speaks. If one doesn’t know the music it seems to me from his account that one will want to.

Walsh’s writing has the clarity of speech, honed from years as a music critic and tested in his magnificent books on Stravinsky. The pleasures of this new book come not only from his deep knowledge of Debussy’s music but from writing that is able to capture Walsh’s own amazement in the face of it. Of the Baudelaire songs he writes: ‘By any standards .. these are wonderfully beautiful songs, but they are also subtle and resonant, images of sensual consciousness that elevate the soul as well as the body, the mind as much as the heart.’ This needs saying, and in the context of Walsh’s whole treatment such an assertion is justified. We trust him. But he also provides musical details - of melodic shapes, intervals, pianistic figurations, orchestrations, rhythmic structures - that never weigh down the commentary, and only enhance what we know we will hear. ‘The exquisitely complex dissonances of Le Martyre de St Sébastien,’ he writes, ‘acquire here a transparency and airiness like the brush strokes in an impressionist water colour.’ Yes they do. We at once want to go to the music to find out, to experience this again or for the first time. Of the Verlaine songs (Trois mélodies) he writes, ‘There is no way that music could sensibly respond to these things [Verlaine’s rich and varied imagery which Walsh clearly relishes] in any graphic detail, but it can leave spaces for the atmosphere to seep in;’ and of Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune that ‘the elaborate languor of Mallarmé’s faun can almost be smelt in this quietly sumptuous, mobile yet inert orchestral texture.’ This is great teaching too.

The subtitle ‘A Painter in Sound’ is perhaps a necessary provocation. To have added a question mark would have been clumsy, but as it stands it makes a statement that Walsh’s deeply nuanced account simply doesn’t make. Yes, he writes with immense discernment about Debussy’s interest in Art Nouveau, and the revolutionary techniques in the visual art of his time. But never once does Walsh make easy assumptions about music and painting, Debussy and Impressionism. His account is impeccably grounded in musical actualities, and whenever he allows himself to muse upon the relationship between sound and sight - certainly a fascinating and valid speculation - he shows himself to be well aware of the pitfalls.

‘The idea behind so-called Impressionist painting was to capture the image very quickly, painting typically in the open air in the presence of the subject, and the techniques involved related to physical matters such as the changing light and the drying speed of paint. Such issues have no meaning to a composer, working indoors in a medium that is not, like the painter’s canvas, the eventual object, but only a set of instructions for its production (that is, performance).’

This would appear to say everything necessary. But it doesn’t quite. Walsh knows that the means by which a work of art is created need have no bearing on the way it is perceived. It is one of the many strengths of this book that Walsh hears the popular view of Debussy’s ‘impressionism’, the one that won’t go away, and pays attention to it.

International Piano/Paul Roberts © 2018